The poetics of recitation

Meeting the man who knows 162 poems by heart

I first encounter Yvan when crossing the Pont des Arts. He’s a tall man dressed like a dapper Charlie Chaplin—black suit, white gloves and a felt bowler hat.

The hat, combined with his sturdy posture and deep diaphragmatic voice, have the effect of making him look even taller—anchored above the otherwise moving Seine.

Yvan is a “diseur,” meaning “reciter.” He has with him a six-page packet of all the poems he knows by heart—in French, German, English and even Polish. In total, they amount to six hours, twenty one minutes and thirty seconds of reciting.

This is my fourth time in Paris, and yet again, I find it a city sure of itself. It’s in the gait of the people, walking the streets with effortless style. It’s even in the weather—clouds that come and go as they please with little regard for forecasting.

This sits in contrast to my Madrid, which shares in Paris’s affinity for sophistication but diverts for a slightly more bohemian flare: linen skirts and flimsy blouses, no umbrellas hooked over the arm. The sun in Madrid is a far more reliable friend. She generally shows up when expected and will, with a little coaxing and the promise of a good time, make an appearance even when she’s had a long week.

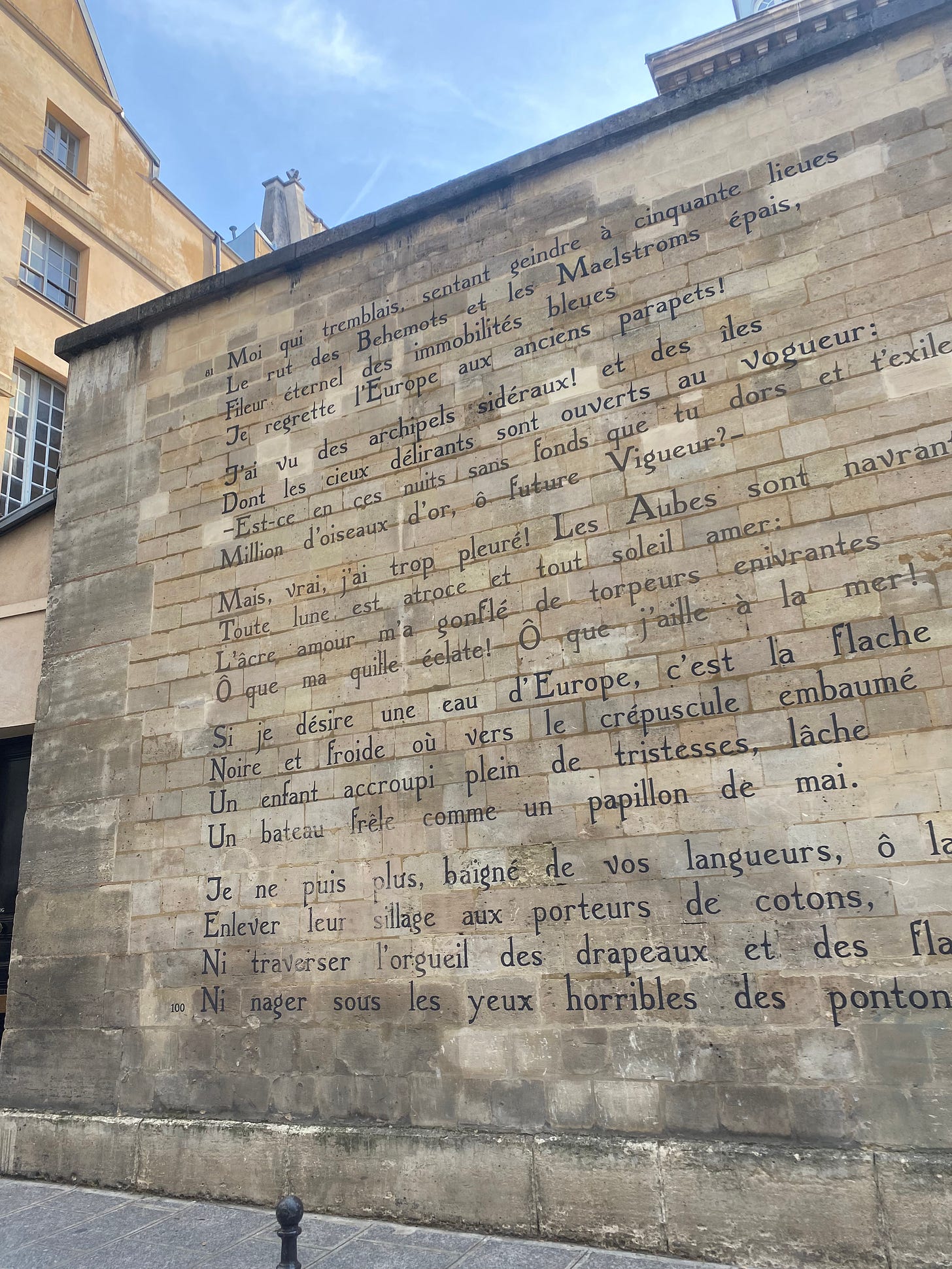

On the list of things Paris is sure of: its affinity for poetry. All 100 lines of Rimbaud’s “Le Bateau Ivre”—number ninety-two on Yvan’s list—are painted on a wall on Rue Férou, steps from the famous Jardin du Luxembourg.

Even the construction of the city reads like a poem; meticulously-crafted Haussmann buildings line both sides of boulevards like rhyming verse, each with a meter of delicately-arranged second- and fifth-floor balconies.

Yvan is just about to recite Wordsworth's “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” when the police materialize. This is no unusual occurrence for Yvan who, after many years of lobbying to the police, and even the mayor, now carries a permission slip for just such occasions.

But the conversation goes differently this time. The summer Olympics is quickly approaching, and they inform Yvan that soon, he’ll have to quit the act. “If we allowed you to stay, we would have to allow all performers to stay,” an officer tells him.

Yvan’s art isn’t the only art at risk due to the Olympics. The bouquinistes—little green open-air stands for antique bookselling that dapple the banks of the Seine—have been permanently fixed since 1859. They were set to be removed for the Olympics, but after a public outcry, the city decided to keep them. Yvan isn’t so lucky.

Such debates beg an important question—just how much culture can you strip of a place before it ceases to be what it was? When the 15 million tourists arrive, will they be able to see the Paris they came for, or will they get in their own way?

Just how much culture can you strip of a place before it ceases to be what it was?

Yvan has been memorizing poems since he was fifteen years old. He doesn’t remember why he started, only that once he did, he never stopped.

He repeats each aloud until he learns it by heart, at which point he immortalizes it in a dedicated notebook. Well, three notebooks now. But always, he insists, with the same ink pen. The ritual is almost spiritual—one that has required him, on several occasions now, to fill the pen with new ink.

On the bridge, I watch a young family of three approach Yvan. The boy picks a poem, and all three settle onto a bench to listen. Once Yvan finishes and they stand to go, the mother kisses the boy on the forehead—a small, inspired act of tenderness.

When I ask Yvan why so much memorization, he tells me the poetry is something he can carry anywhere he goes. “It weighs nothing,” he says.

I think of the poems I’ve memorized over the years—poems that came to live with me like friends. In a period of intense loneliness, I memorized Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s “Solitude” which, in its expression of isolation, had the effect of making me feel less so:

There is room in the halls of pleasure

For a large and lordly train,

But one by one we must all file on

Through the narrow aisles of pain.

I would even, at times, take comfort in reciting my own poetry as if my past self were speaking to me. “Tell me, is today blue? / And I’ll sit and share air in your room.”

Watching Yvan recite another poem with not a hint of hunch in his shoulders, I wonder if poetry is more than just weightless. Perhaps it has some kind of buoyancy—a way of lifting you up out of yourself.

I wonder if poetry is more than just weightless.

Perhaps it has some kind of buoyancy—a way of lifting you up out of yourself.

Yvan’s list had 160 poems in total, though he admitted, with a smirk, “It’s actually 162. And the last two are a good story…”

He tells of a teacher who paid his fare to Germany to come and read to her students. There, a young German boy recited Paul Eluard’s “Dans Paris.” So moved by the boy’s performance, Yvan bought the book when he returned to Paris and began memorizing. Not a week after committing the poem to memory, someone stopped along the bridge and asked, “Do you know any poems about Paris?”

I asked Yvan if he had a large collection of books by this point, to which he shook his head. “I don’t keep them,” he said. “Once they make it into the notebook, I don’t need them anymore.”

In fact, he told me he had tried to donate “Dans Paris” to a local library, but they turned him away. So he got on a bus, placed the book on a seat, and sat in the row in front of it.

A few minutes later, a woman and her daughter got on. “Regarde!” the girl shouted, pulling her mom to the book. Yvan listened as the girl read aloud behind him. A few stops later, the duo got off, carrying the book to its new home.

I ask Yvan if he ever recites the poems when he’s alone. He tells me of the many times he’s employed a poem to accompany him down a particularly hideous street, or to get him up seven flights of stairs. “I say the poem, and by the time it’s over, I’m at the top.”

“These white plastic things,” he says, pointing to his ears. He tells me everyone is wearing them to avoid the aggression of everyday life. I can feel mine burning hole in my pocket as he tells me that for him, they have never been necessary. The recitation is, as he sees it, “an antidote to all that is ugly in the world.”

“[Poetry recitation is] an antidote to all that is ugly in the world.”

I ask Yvan if he writes too, and he insists he doesn’t. “I did write one poem though.” He tells me it came to him at three in the morning, a week after his father died. He jotted it down, knowing it wouldn’t stick around if he waited until morning. “He was a man I thought very highly of,” he says. He then committed that poem to memory, the 162nd. I ask if he will recite it for me.

This one is shorter than the others, but every word is articulated with a kind of reverence. Eyes fixed on the horizon, he speaks of his late father, living somewhere new “across town.” Can his father remember him? Will they still recognize each other with time?

There is something in his voice—something like pain—but his pitch doesn’t waver at all. He is sturdy and rooted, a well stretching down to the Seine. Up from his diaphragm flows language drenched in memory. I suspect it will never run dry.

Yvan will have to find another place for a while. But I don’t worry much for him, or for Paris. Even when throngs of people stand on the Pont des Arts, the Seine will keep flowing underneath it. And eventually, Yvan will return, as will the musicians and the painters, each drawn by the poetry of the city; each, in turn, ready to remember.

Were the cops busting him specifically for reciting Wordsworth? I can imagine them radioing back to dispatch. "We've got a 334, English Romantic in progress. Suspect is rhapsodic. I repeat, suspect is rhapsodic, possibly intoxicated by the majesty of nature. Backup requested."